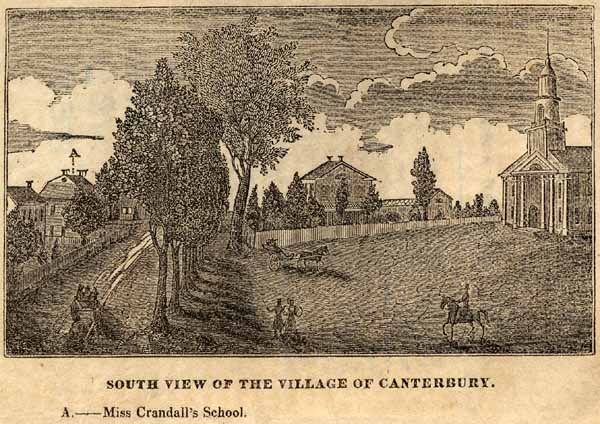

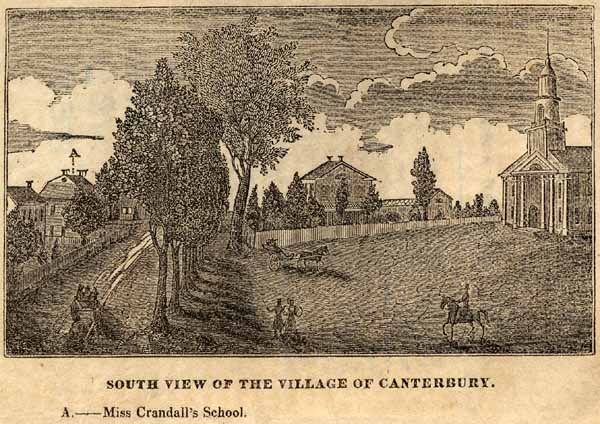

The Canterbury Female Boarding School is at the top center of this newspaper clipping.

At the Canterbury Female Boarding School, Prudence Crandall offered instruction in “reading, writing, arithmetic, English grammar, geography, history, natural and moral philosophy, chemistry, music (piano), and French”. I am searching for historical evidence of what she may have taught so we can develop a classroom scene for the play.

I reached out to Kaz Kozlowski, long time curator at The Prudence Crandall Museum, in hopes that she might have a textbook or lesson that Crandall used with her students. Kaz told me she did not and added that teachers were “free to use reading materials and books on specific topics more freely than they are today”. She does, however, have a copy of The Schoomaster’s Companion, which provided teachers and schoolmasters with guidelines for setting up classrooms and organizing school materials. You can bet I plan to go see that book.

Meanwhile, I have been left trying to deduce what Crandall may have taught. From my experience as a teacher, I know that I created lessons from texts with which I was familiar as a student; Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style was always part of my curriculum.

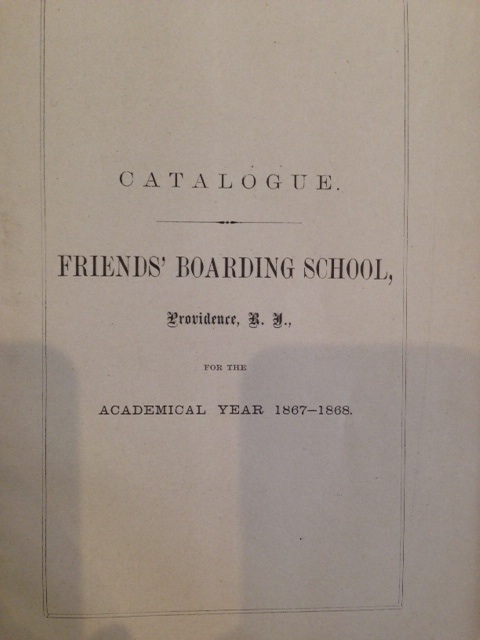

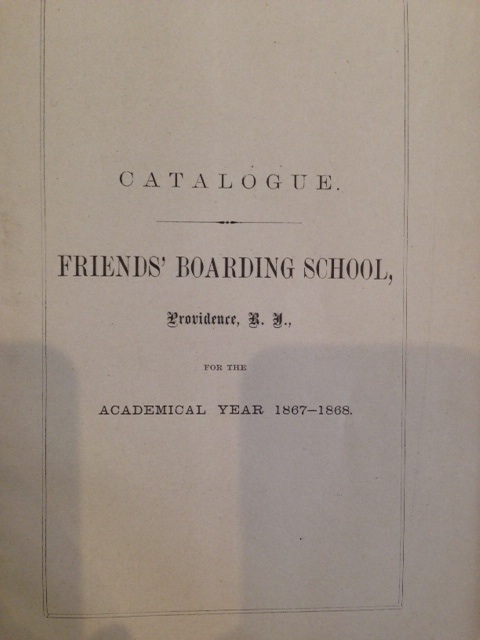

In pursuit of this theory, I reached out to the Moses Brown School in Providence, Rhode Island (formerly The Friend’s Boarding School) to see if they have any schoolbooks from Crandall’s time as a student there (circa 1826). Anne M. Krive the MBS Middle School Librarian was not able to find any primary sources from the 1820s, but she did find a catalog that was in use at the school from 1867-1868.

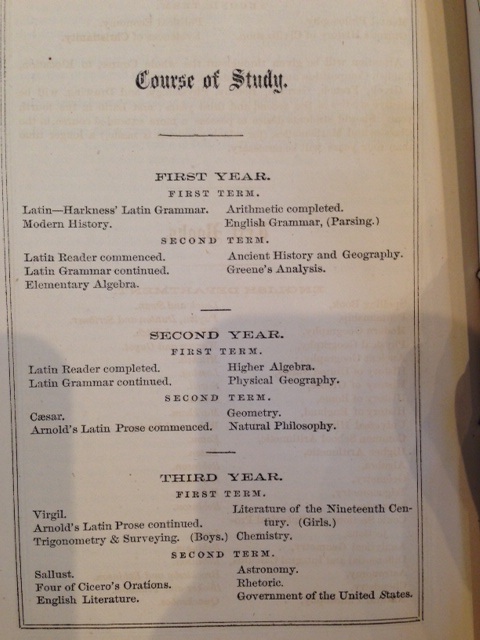

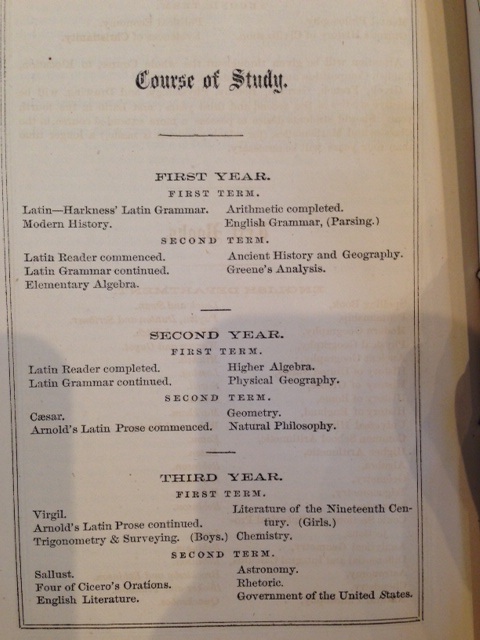

The “course of study” of this “academical” year includes the following courses and terms:

This more specific list of subject matter and authors can help me target possible books Crandall may have used — with the caveat that this course of study is for a period more than 30 years after Crandall taught.

The Friends’ Boarding School was a Quaker school and so it admitted both boys and girls. In addition to abhorring slavery, Quakers promoted gender equity in “meeting” and with regard to education. However, a little close reading of the above course of study shows that in the first term of the third year gender lines were clearly drawn with “Trigonometry & Surveying” required of the boys and “Literature of the Nineteenth Century” required of the girls. The lack of women in STEM careers has roots in an American system of education that diverted women from a course of study that would have provoked their interest in advanced science and math.

The following photo is from 1898 — much later that when Crandall attended school — but this provides an interesting perspective on mixed gender science classrooms during the Victorian era. (Anatomy and physiology class, no less! How terribly risque…)

On Wednesday, March 5th, I will travel to the Moses Kimball School to meet with Anne and the school archivist. I will let you all know what I dig up.